How does the current US system of international taxation work?

All countries tax income earned by multinational corporations within their borders. The United States also imposes a minimum tax on the income US-based multinationals earn in low-tax foreign countries, with a credit for 80 percent of foreign income taxes they’ve paid. Most other countries exempt most foreign-source income of their multinationals.

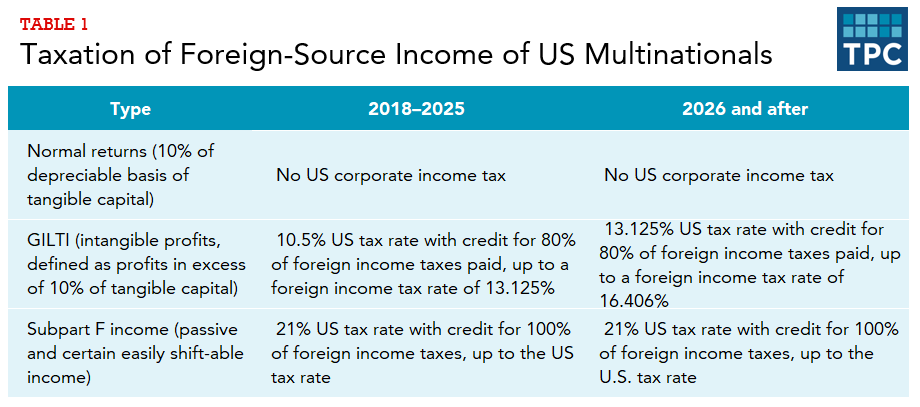

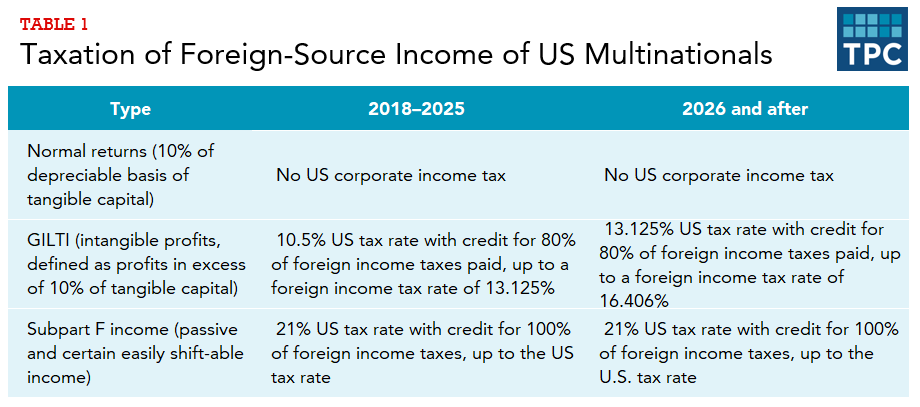

Following the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the federal government imposes different rules on the different types of income US resident multinational firms earn in foreign countries (table 1).

US companies can claim credits for taxes paid to foreign governments on GILTI and subpart F income only up to their US tax liability on those sources of income. Firms may, however, pool their credits within separate income categories. Excess foreign credits on GILTI earned in high-tax countries, therefore, can be used to offset US taxes on GILTI from low-tax countries. US companies may not claim credits for foreign taxes on the 10 percent return exempt from US tax to offset US taxes on GILTI or subpart F income.

Suppose, for example, a US-based multinational firm invests $1,000 in buildings and machinery for its Irish subsidiary and earns a profit of $250 in Ireland, which has a 12.5 percent tax rate. It also holds $1,000 in an Irish bank, on which it earns interest of $50.

TCJA also introduced a special tax rate for Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII)—the profit a firm receives from US-based intangible assets used to generate export income for US firms. An example is the income US pharmaceutical companies receive from foreign sales attributable to patents they hold in the United States. The maximum rate on FDII is 13.125 percent, rising to 16.406 percent after 2025. FDII aims to encourage US multinationals to report their intangible profits to the United States instead of to low-tax foreign countries.

Most countries, including all other countries in the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom), use a territorial system that exempts most so-called “active” foreign income from taxation. Still others have hybrid systems that, for example, exempt foreign income only if the foreign country’s tax system is similar to that in the home country. In general, an exemption system provides a stronger incentive than the current US tax system to earn income in low-tax countries because foreign-source income from low-tax countries incurs no minimum tax.

Many countries also have provisions, known as “patent boxes,” that allow special rates to the return on patents their resident multinationals hold in domestic affiliates.

Most other countries, however, also have rules similar to the US subpart F rules that limit their resident corporations’ ability to shift profits to low-income countries by taxing foreign “passive” income on an accrual basis. In that sense, even countries with a formal territorial system do not exempt all foreign-source income from domestic tax.

Countries, including the United States, generally tax the income foreign-based multinationals earn within their borders at the same rate as the income domestic-resident companies earn. Companies, however, have employed various techniques to shift reported profits from high-tax countries in which they invest to low-tax countries with very little real economic activity.

The US subpart F rules, and similar rules in other countries, limit many forms of profit shifting by domestic-resident companies but do not apply to foreign-resident companies. Countries use other rules to limit income shifting. For example, many countries have “thin-capitalization” rules, which limit companies’ ability to deduct interest payments to related parties in low-tax countries in order to reduce reported profits from domestic investments.

TCJA enacted a new minimum tax, the Base Erosion Alternative Tax (BEAT) to limit firms’ ability to strip profits from the United States. BEAT imposes a 10.5 percent alternative minimum tax on certain payments, including interest payments, to related parties that would otherwise be deductible as business costs.

Dharmapala, Dhammika. 2018. “The Consequences of the TCJA’s International Provisions: Lessons from Existing Research.” Prepared for National Tax Association, 48th Annual Spring Symposium Program, Washington, DC, May 1.

Gravelle, Jane G. and Donald J. Marples. 2020. “Issues in International Corporate Taxation: The 2017 Revision (P.L. 115-97).” CRS Report R45186. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Updated February 20, 2020.

Joint Committee on Taxation. 2015. “Issues in Taxation of Cross-Border Income.” JCX-51-15. Washington, DC: Joint Committee on Taxation.

Kleinbard, Edward D. 2011. “The Lessons of Stateless Income.” Tax Law Review 65 (1): 99–172.

Morse, Susan C. 2021. “The Quasi-Global GILTI Tax.” Pittsburgh Tax Review 18.

Shaviro, Daniel N. 2018. “The New Non-Territorial U.S. International Tax System.” Tax Notes. July 2.

Toder, Eric. 2017. “Territorial Taxation: Choosing among Imperfect Options.” AEI Economic Perspectives. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.