Editor’s note: In the first post in this series, Perry discussed how stories help people live by cementing social bonds, and enabling humans to see the consequences of actions through the choices of characters. She also talked about how our brain responds to compelling narrative, using this to explain why stories can be so captivating. Now, in the second part, Perry describes how stories can evoke strong feelings of empathy and why this occurs. In part three, she will connect what this all means for advocates.

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

Imagine: It is hot, the kind of heat that feels as if it is personally out to get you. Your mouth is dry, your tongue sticky like tape.

But not for much longer.

Up ahead you see a clearing, and the reflection of sun hitting water. Anticipation animates you.

Cupping your hands, you scoop water to your lips again and again until your stomach aches. You can’t get enough. It’s splashed onto your face and then smoothed back into your hair.

But like all good things, your peace is not to last. Satiated now, you become aware of a form, small and burning red under the sun. A child! The child is lying in the field, watching you under heavy eyelids. Glassy eyes, weak limbs, burning skin, parched lips. This child is too hot.

You quickly fill your water bottles, wasting no time.

But it is not the watching child you run to. It is distant and waiting shade.

The trees provide relief. They would have sheltered the child but that doesn’t matter.

The only thing that matters is that you are not the child and his thirst is not your own.

Consider how different society would look, despite its current problems, if every time we encountered suffering we responded with the emotional equivalent of shoulder shrugging.

Therefore, empathy, or feeling another person’s pain, is integral to societal and community functioning. Without this ability we would be significantly less likely to take actions to help others.

Emotions are important because they motivate us. Knowing that something is important is helpful, but it can’t compare to feeling that same knowledge.

With empathy, for example, we not only notice that a child is thirsty and viscerally feel their suffering, but have a strong desire to give them water. In fact, failing to help the imaginary child above would have caused the average person actual heartache.

War has built empires, but it is empathy and love that has sustained the human species.

This is why empathy, and those things which foster it, have always been and will always be important.

Stories are empathy workhorses.

In this post, I’m going to share three main ideas related to effective storytelling.

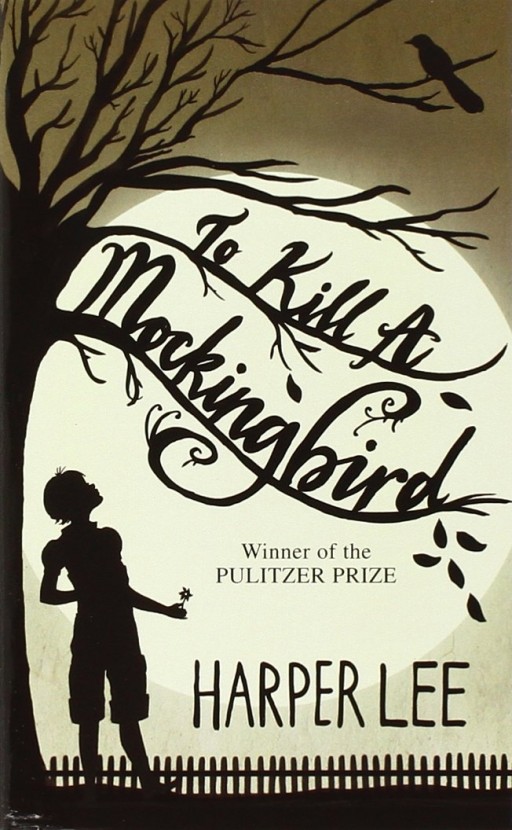

Reading high- (but not low-) quality fiction may translate to real-world empathy and theory of mind abilities, according to a study recently described in The Guardian.

This is because the artful narrative of the type associated with books in a literature course creates characters that have depth and ambiguity. Thus, when reading this type of writing, according to David Kidd, one of the lead authors on the study, readers must try to “understand the minds of others” in the book.

Specifically, this study found that participants who read “literary fiction” were better able to “detect and understand other people’s emotions” than those who were given entertainment fiction to read.

(For the curious, this study defined literary fiction as books that were finalists for the U.S. National Book Award and that were PEN/O. Henry award winners).

But storytelling does not automatically generate empathy, according to researchers in Amsterdam. For the milk of human kindness to really get flowing, readers must be transported. Transportation is the magic that happens when a story has your full mental and emotional attention.

Taking a slightly different perspective from the study discussed above, the study “ Does Fiction Reading Influence Empathy? An Experimental Investigation on the Role of Emotional Transportation“ was specifically designed to measure if reading fiction increases empathy, and if transportation explains this increase.

To answer this question , the researchers controlled for the participants’ innate level of empathy, and used two different experiments.

Experiment One

In the first experiment, participants were divided into two different groups.

To put this another way, the researchers wanted to see how those participants who read the “Sherlock Holmes” passage, and who were also transported, would compare in terms of empathy to two groups:

Results from this first experiment were significant. Participants who both read fiction and were transported reported greater empathy than those were not transported. For these readers, as transportation increased, so did empathy. Even more interestingly, those participants in the fiction group who were not transported actually reported decreasing empathy. Empathy and transportation were unrelated for the newspaper readers.

Experiment 2

But these researchers were committed, so they decided to include a second experiment in the study.

This second experiment was designed to replicate the results of the first experiment, described above, but used an excerpt from the book “Blindness” and a different set of newspaper articles . “Blindness,” true to its title, explores what happens when its protagonist suddenly loses his sight. This second experiment also had participants rate the degree to which they experienced positive and negative emotions after reading the excerpt.

The results from the second experiment, similar to the first, found that when people read fiction and aren’t transported, empathy can actually decrease.

In sum, these findings suggest that when readers are presented with a story yet fail to enter into the world it creates, they cannot respond empathetically because they never engage with its characters. Transportation matters.

Others have suggested that fiction increases empathy because people who read a lot may be more attuned to social nuances ; fiction consistently simulates real-world social landscapes .

That being said, it is hard to control for the fact that maybe people who love fiction are more empathetic to begin with.

The ability of stories to create empathy is especially highlighted through a couple of research studies from the 1960s and ‘70s . In one, researchers found that white children who heard a story featuring a black protagonist/child had improved attitudes toward black children.

Similarly , another study found that second-grade students who read stories featuring black and other racial minority children were more likely to include black children in their own social group and reported more positive views of black people, than children who read stories with white main characters.

In this second experiment called “ Changes in attitudes toward Negroes of white elementary school students after use of multiethnic readers ,” the authors commented that there is research showing that direct experience with people of different races can reduce bias. However, during the era in which this study was conducted, white children were infrequently exposed to black children, ensuring that they would internalize racism.

Therefore, the study authors posited that stories featuring children of different races could substitute for direct positive experience for the white children, and fight back against the widespread racism they were internalizing.

One way the study authors helped the white children think positively of the black children they were reading about was to ensure that the black children had middle-class indicators.

For example, the children were described as well dressed and hard-working. (This of course reveals the degree to which poverty was associated with negative characteristics and bias, much as it is today.)

Children in the control condition were exposed to the same stories as those in the experimental condition, but with white characters.

The results from the study were significant. Across all post-test measures designed to assess changes in racial attitudes, children exposed to stories about multiethnic and black children showed attitude improvement. In other words, they viewed black children more favorably.

These findings highlight how stories can be vehicles for empathy and the fostering of social inclusion. Moreover, they suggest that using stories intentionally to reduce bias would still work today, and not just for children.

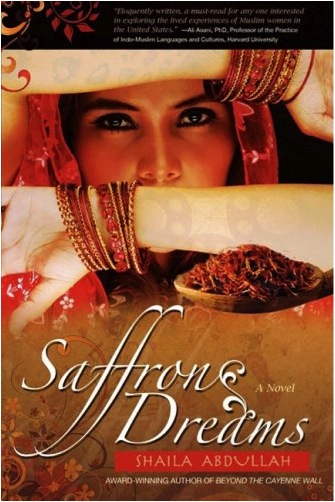

Along these lines, in today’s world psychologists are now using fiction to see if it can generate shifts in racial stereotypes, according to an article written by Dr. Jaless Rehman for the Huffington Post.

The study authors decided to measure a shift in racial stereotypes in an intriguing way. After the different groups read their assigned text, they were presented with 18 male faces that were racially ambiguous and could be inferred to be either white or Arab, or a mix. They were then asked to determine if the faces were white, Arab, or mixed/more white, or mixed/more Arab.

Participants were also asked to guess the amount of genetic overlap, or DNA, that is shared between white and Arab people. (Spoiler: it is basically 100 percent; the question was included to assess the degree to which the “Saffron Dreams” passage fostered inclusiveness.)

The results backed up the power of fiction to break down bias, albeit in a round-about way:

In another segment of the study , a different group of participants was asked to examine the same racially ambiguous faces, but this time with the faces expressing varying levels of anger. These participants were asked to read either about cars, the actual excerpt about the Muslim woman, or the summary. Those participants who had read about cars or who had read the summary were disproportionately likely to rate angrier faces as completely Arab. However, those who read the fictional account of the Muslim woman did not display this bias.

Like the psychologists who used fiction to break down racism in children in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the researchers concluded that high-quality storytelling provides a way to humanize out-groups and cultures. They note: “ there is growing evidence that reading a story engages many of the same neural networks involved in empathy.”

And this conclusion mirrors the theoretical orientation behind the study on transportation and empathy discussed earlier. The study authors write that the evidence suggests that “seeing or reading about another person experiencing specific emotions and events activates the same neural structures as if one was experiencing them oneself, consequently influencing empathy.”

However , one of the clearest examples of the ability of stories to evoke empathetic responding involves an experiment developed by a researcher named Paul Zak, with the Center for Neuroeconomic Studies at Claremont University in California.

Dr. Zak and his colleagues are interested in why stories are powerful, and more specifically, how hearing a compelling story drives prosocial action. Therefore, they designed an experiment using a story specifically designed to evoke empathy.

Here’s how the experiment goes down:

Participants watch a video that tells the story of a father and his young son Ben, who has terminal cancer and will soon die. The father says that it is hard to play with his toddler son, knowing that he has only a couple more months to live. This is contrasted against Ben’s emotional state, which is described as quite happy because he cannot grasp his own impending death. (Ben’s story is true, by the way.)

They studied how participants responded to this video , and then connected this to what creates a powerful story, and more particularly, what motivates giving to charity. For instance, they have found that half of participants who watch the video donate the money they earned for their participation in the experiment to a childhood cancer charity.

This highlights an important concept in storytelling: it is not so much the “realness” of the story that matters in eliciting empathy, as it is the structure. So a non-fiction event that uses storytelling features and structure can evoke as much empathy as a fictional narrative.

What separated those who gave money from those who didn’t? Two very basic things had to happen:

Zak states that those who did give were happier and were more empathetic than those who did not give. Why they were happier, and how they were measuring empathy (self-report?) to capture these traits was unclear in the article.

Let’s break down attention first. How do storytellers get and maintain it? How do they ensure their audience is transported?

According to Zak and his team, attention is captured when the storyteller slowly builds the tension in the story. That is, truly powerful stories have a dramatic arc. As the audience’s attention holds, they become absorbed by the lives of the story’s characters and stress hormones are released. This causes audience heart rate and respiration rate to actually increase. This is because the brain thinks anything that holds its attention is important.

Then, once their attention has been caught long enough, the audience enters into the world of the characters. At this point the reader or audience is now in a mental state that enables “transportation,” where they sweat, ache and laugh along with the characters in the story. The lives on the page or screen have become real.

Now, the hurts and triumphs of the characters are felt intimately, an emotional resonance that is profound , given that stories are merely words on paper, sounds in air, or images on a screen.

No wonder we call good storytelling “spellbinding , ” and “mesmerizing.”

Zak and his colleagues have identified that oxytocin is the hormone that facilitates this transportation. That is, compelling character-driven stories capture our attention and facilitate its release, enabling us to inhabit new worlds of the author’s invention.

Oxytocin is the same hormone, that, when released, makes people more compassionate, more charitable, more generous and more trustworthy. It also makes people notice social cues better, thus making them more likely to help someone in need. In short, it puts people in a frame of mind that is great for cultivating advocacy.

Thus, the emotional simulation provided by compelling storytelling provides a neural foundation for empathy, and provides insight into why well-crafted stories are such powerful advocacy tools.

To me this helps explain the success behind storytelling projects like StoryCorps and The Moth . When the audience hears the story of a mother experiencing homelessness, on a certain level they are no longer in their own world, but in hers.

And it is possible that this immersion differs based on medium.

Zak says the film of “Ben’s Story” does a better job of eliciting empathy than the written version, suggesting that film might provide a more evocative experience .

This emergence into another world via film can lead to an interesting effect once the film ends. Zak has found that after watching a film, viewers mimicked the feelings and behaviors of characters they had just watched on the silver screen once the story ended. Zak explains that this is why a good action movie can have you leaving the theater feeling pumped up.

Similarly, a meta-analysis conducted by media psychology researchers Mare and Woodard (2005) found that television shows that explicitly emphasize empathetic and kind behavior can lead to positive behavior change in children. This is probably related to the fact that children learn through what is modeled for them, both in their family and in society. So just like an action movie can have viewers leaving the theater ready to take on the world, stories which highlight morality and empathy can lead the audience toward those values (at least if they are children).

So now we know that when people hear a compelling empathy-evoking story, their brain synthesizes oxytocin. But we also know that for a story to motivate action it must do more than evoke empathy; it must also capture and hold our attention, transporting us into the world of the character.

And, when story is used in connection to charity, people may feel moved enough to give money or time to a social cause. Thus, stories cultivate mental states that increase the likelihood of advocacy.

Finally, stories can be used to break down bias, cultivating the awareness that superficial and exploited differences like race are nothing compared to our commonalities.

Coming next in part 3 in our series on storytelling: How nonprofits and advocates can use stories to increase empathy and drive prosocial change. This post will tie together the evolutionary roots of stories and their role as empathy facilitators into concrete recommendations for those using stories intentionally to motivate action.

Thank you so very much for this text. I am trying to use the power of stories to connect cognition, emotion and spirit in a University course on Determinants of Health and Disease. I know intuitively that stories enhance empathy, but the research presented here really helps to anchor this intuition in reliable foundations. Great text!

It really is a thoughtful entry–I’d love to see it published in an academic or trade journal to add to its credibility. Maybe Poets and Writers or The Writing Chronicle. Love this!