Here’s what experts and hiring managers look for in your graphic design portfolio.

Written by Jeff Link

To be a successful graphic designer, a standout portfolio is essential.

It can be a challenge to catch the attention of recruiters and clients, though — they may only spend a few minutes reviewing your portfolio, so it has to make an impression from the get-go.

And while there’s no standard approach to crafting a graphic design portfolio, keeping a few expert-approved tips in mind may help you stand out from the pack.

To the broader public, the term graphic design applies to virtually any type of digital design. The design ecosystem, however, tends to be discipline-specific. Drilling down on the type of work you want to do, whether that’s creating logos or custom illustrations for a digital branding agency, designing social media cards for a marketing department, or working on an app’s iconography as part of a product team, can be crucial to landing an interview.

“I started as a designer eons ago,” Michael Sacca, former chief product officer at the design portfolio platform Dribbble, said. “The biggest mistake I made, which applies at Dribbble, is not making it clear what you do well. You might be okay at everything, but what do you excel at and where have you focused your attention? Make a decision: You can’t be everything to everyone.”

Give the hiring manager a glimpse of your personality. A short bio on the landing page of a personal web portfolio can illustrate this well. On Almost Studio’s website, multidisciplinary designer and founder Odes Roberts introduces himself in a large, sans serif font that dominates the screen. A biography on the “about” page gives viewers an immediate sense of who he is and how that identity manifests in his design ethos. “Everything real comes from honesty,” the site announces candidly.

That touch of individuality can make a difference, not only to potential clients, but to hiring partners.

“When you’re hiring, you’re not just hiring a set of hands, you’re hiring a brain, you’re hiring somebody with lived experience, everything they’re bringing with them,” Michael Johnson, executive director of design and experience at agency Happy Cog, said. “And however that comes through, that’s something that I’m definitely looking for.”

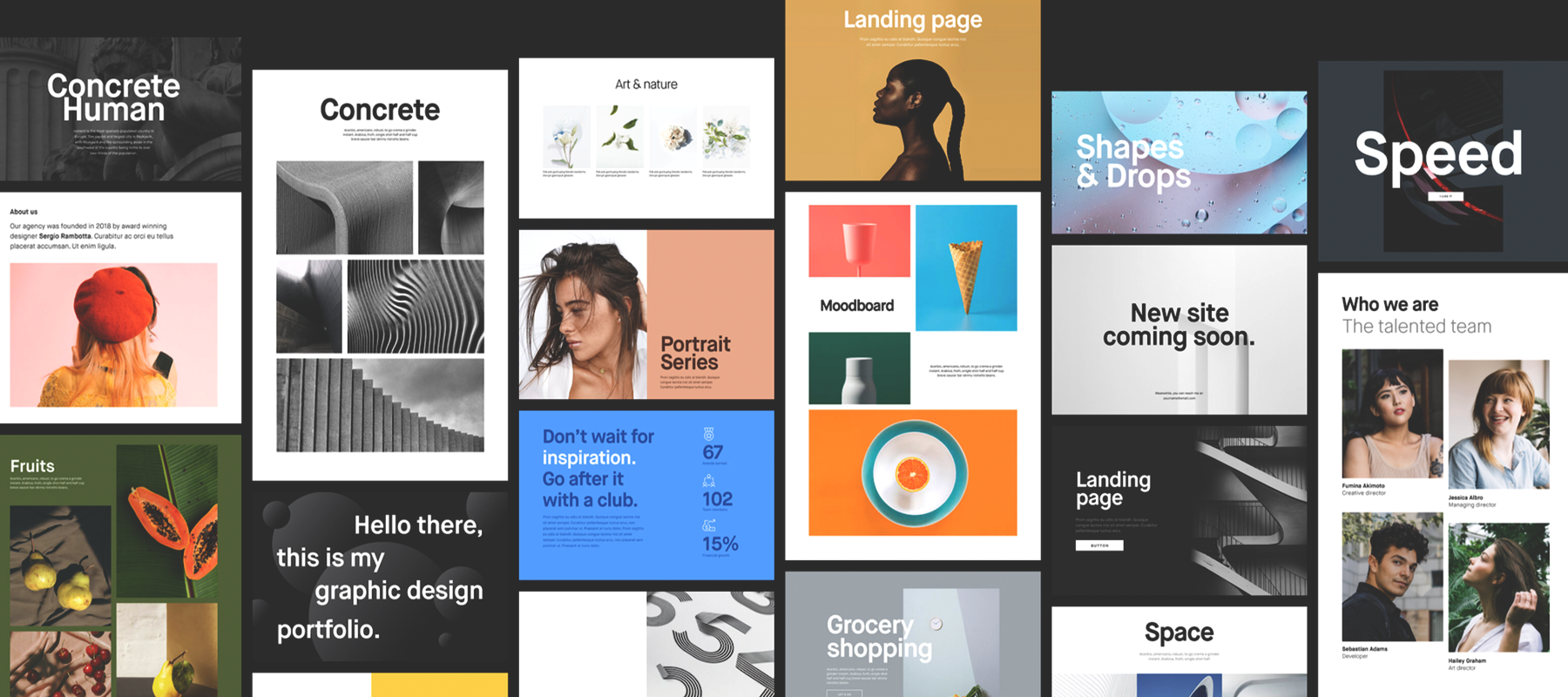

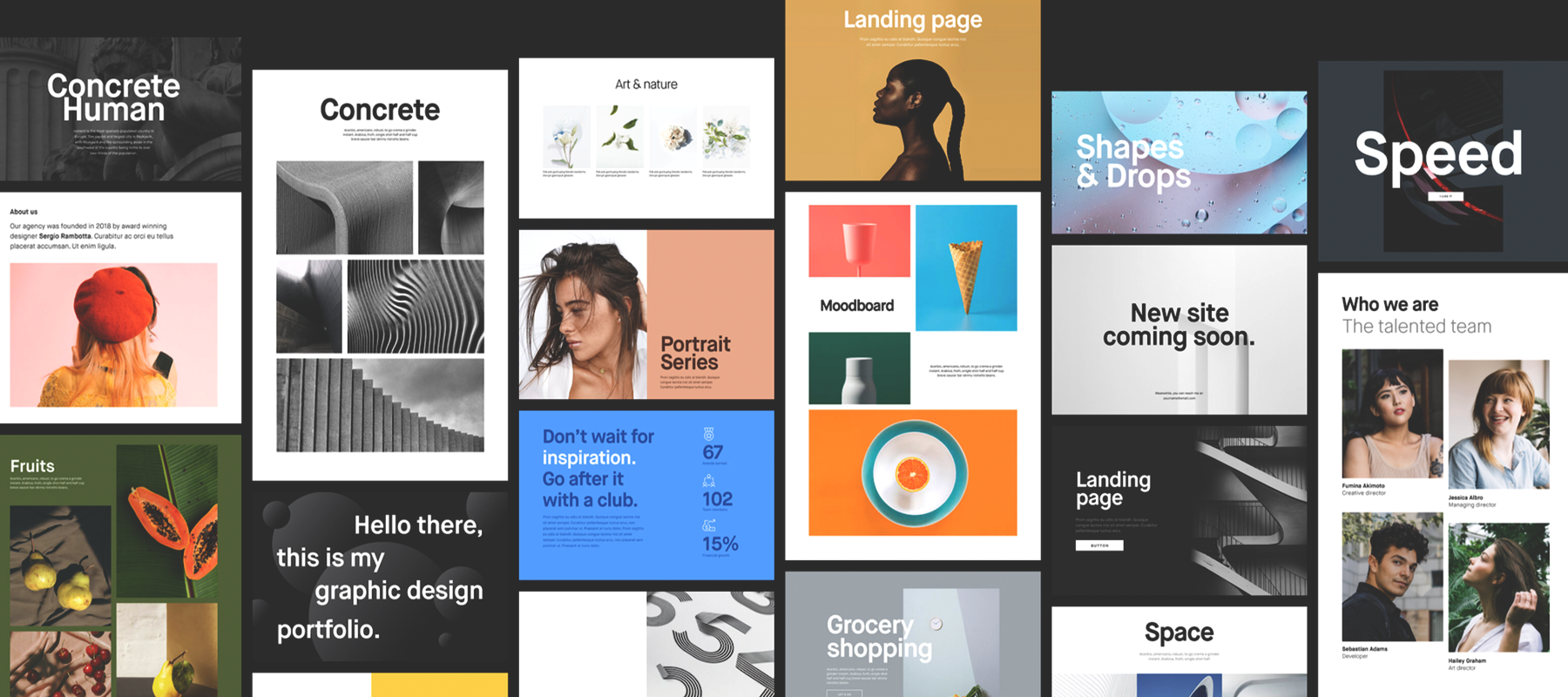

A web portfolio is a good place to house a gallery of case studies that showcase the breadth of your work. Whether this is scratch-created or produced from a template, the important thing is that the layout matches the designer’s personality.

“There are tons of website builders out there: Webflow, WordPress or Squarespace,” Roberts said. “The main thing that needs to come out is you, not only you as a designer, but you as a person because that’s what sells what you know how to do.”

Roberts showcases work by clients such as Shutterstock and Northwestern Mutual, as well as more personal projects like MixTapes (in which he designs cover art for friends’ playlists) on a carousel because it reflects his design sensibility. “I enjoy a little bit of interactivity when I look at something,” he said. But other designers may prefer another format — a masonry grid or a long page of stacked cards — and that’s just fine, as long as it reflects their distinctive points of view.

That said, portfolio builders like Semplice can help spark ideas. Many template-based sites offer drag-and-drop workflows and options for interactive features such as page transitions, block layouts, cover effects and split grids.

It’s easy to overplay the interface gymnastics, though. When it comes to the layout, what you really want to do is arrange your work in a way that is direct, accessible and easy for a hiring manager to navigate.

“You don’t need to reinvent the wheel,” Cielle Charron, a freelance graphic designer and instructor at Portland State University, said. “I think UX and UI designers, especially, feel they need to make something completely new and completely custom. But in reality, the portfolio should be more about the work than the format itself.”

Yet the form of the written content is often its own proof of competency. Sacca recommends structuring the narrative hierarchy of each case study after author Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle model, a value proposition that leads with “the why.”

“Why does the project matter?” Sacca paraphrased it. “What problem were you solving and how did you solve it? That should be your opener.”

The framework doesn’t necessarily follow conventional wisdom, he added: “The problem isn’t that you got hired to design a dashboard. Why did you get hired to design a dashboard for the client, and what problems does it solve for the people using it?”

Roberts is unequivocal in his belief about the function of design: “Design is not art. Design is solving problems. Art is for whatever you do outside of design.”

Not all designers share this view, but many will tell you that treating a portfolio like a pristine art object sends the wrong signal.

“We don’t hire designers for their technical skills,” Sacca said. “The medium in which you create — Sketch, Figma or Photoshop — doesn’t matter as long as you’re open to learning and adjusting to the company’s method. Tools can be learned: the deciding factor is how you approach problems and solve them.”

While showing off your mastery of design tools is helpful, it doesn’t get at the core of who you are as a graphic designer. Explaining how you address different challenges and tasks is just as important as proving that you can deliver an eye-catching final product.

“From a hiring perspective, you want to know the kind of person that you are hiring,” Charron said. “Not just that they can make beautiful work, but how do they arrive at that? What is their process like? So thinking about how in a portfolio you can show not only the glossy, beautiful final product, but also the messy bits in between.”

For each featured project, this might include a brief description that outlines the goals of a creative brief or project assignment, describes the designer’s role, and includes web pages, sketches, wireframes, user testing studies and other visual artifacts that trace the narrative of the project.

“Explain what your role was in the project and how you felt about it,” Roberts said. “Two to three paragraphs, max. Everything else should just be a visual of how you actually work.”

Design doesn’t operate in a vacuum, and failure to acknowledge one’s colleagues can leave a smudge on an otherwise strong portfolio. In fact, it’s one of Johnson’s biggest pet peeves.

“If you have been working at an agency or studio or whatever, you had partners in this work,” he said. “You may have had a strategist or researcher help you. You had a creative director, an art director, who might have been guiding the work. Anybody who is involved in the work deserves a mention and it can be terribly frustrating and feels almost deceptive when you get somebody in a room who has misrepresented their contribution to this great, big beautiful thing when what they did was, maybe, put the style guide together. And it can harm your reputation.”